The Hall-Mills Murders

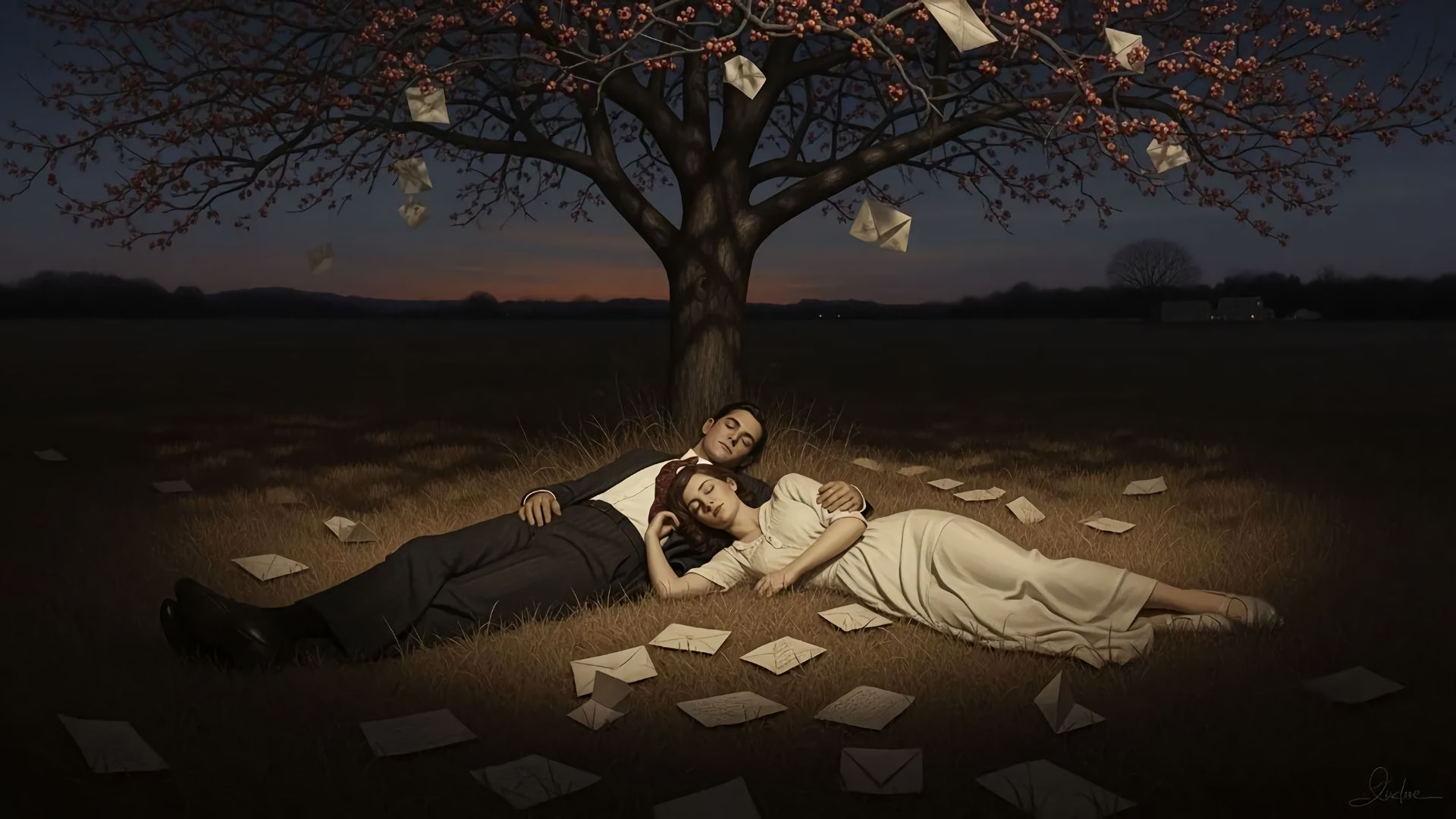

In the autumn of 1922, in a quiet corner of New Jersey, two bodies were found lying side by side beneath a crabapple tree. The man was a married Episcopal minister. The woman was a beautiful choir singer from his parish. Both had been shot in the head, their bodies carefully arranged as if in a lover’s tableau.

The story of their affair and violent end gripped America. Newspapers couldn’t get enough of the scandal, the respectable clergyman, the secret romance, the whispers of jealousy, and the question of who pulled the trigger. It was a tale of passion, betrayal, and social hypocrisy, playing out against the glittering backdrop of the Roaring Twenties.

The case was officially known as the Hall-Mills murders, after the victims: Reverend Edward Wheeler Hall and Eleanor Reinhardt Mills. The investigation and sensational trial that followed revealed not only a tangled web of lust and resentment but also a society obsessed with wealth, appearances, and moral decay, themes that would later echo through F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby.

The Reverend and the Choir Singer

Edward Hall was the rector of St. John the Evangelist Episcopal Church in New Brunswick, New Jersey. Charismatic and ambitious, he came from an old, respected family and was married to Frances Stevens Hall, a woman of social standing and considerable wealth. Their marriage, at least in public, appeared steady.

But behind the facade, Reverend Hall was restless. He was passionate about his work, yet he was drawn to admiration and adoration, particularly from the women in his congregation. Among them was Eleanor Mills, a soprano in the church choir.

Eleanor was 34, married to James Mills, a janitor and night watchman, and the mother of two children. She was vivacious, romantic, and intelligent, but her life felt ordinary and confining. Edward Hall offered excitement, poetry, and attention. Before long, the two began a clandestine affair that would end in bloodshed.

A Dangerous Romance

Their relationship became the talk of the parish. Parishioners whispered that they were seen together too often, walking through the churchyard or exchanging glances across the pews. The gossip grew, but neither Hall nor Eleanor seemed to care.

The pair wrote dozens of letters to each other, filled with declarations of love. They met secretly in the countryside, away from prying eyes. One of Eleanor’s close friends later said that she had become convinced Hall would leave his wife.

But Frances Hall was no fool. She was older than her husband, proud, and fiercely protective of her family’s reputation. Her brothers, Henry and William Stevens, were influential men with money and political connections. Frances had endured rumours before, but this time, the scandal threatened to humiliate her publicly.

By early September 1922, tensions around the Hall and Mills households were high. Eleanor’s husband had also begun to suspect that something was going on.

The Discovery

On the morning of 16 September 1922, a group of local teenagers wandering through a rural area known as De Russey’s Lane made a gruesome discovery. Beneath a crabapple tree lay the bodies of Reverend Hall and Eleanor Mills.

The scene was surreal. The couple’s bodies were positioned close together, with the minister’s arm placed protectively around Eleanor. His Panama hat covered his face. Her scarf had been wrapped tightly around her neck, and her throat had been cut. Both had been shot, Hall once through the head, Eleanor three times.

Scattered around them were torn love letters, many of them written by Eleanor to Hall. It looked almost theatrical, as if the killer wanted the world to know exactly why they had died.

A Town in Turmoil

The news spread rapidly through New Brunswick. Within hours, crowds were gathering near the crime scene. Reporters arrived from New York and Philadelphia, turning the sleepy town into the centre of a national scandal.

The police were overwhelmed, and the investigation quickly descended into chaos. Souvenir hunters trampled the scene, stealing items from the ground. A cigarette butt here, a torn note there, potential evidence was pocketed by curious onlookers before it could be collected.

The obvious question was: who would want them dead? Theories spread like wildfire. Some suspected Eleanor’s husband, James Mills, a quiet man who claimed to have been home asleep on the night of the murders. Others pointed to Frances Hall and her wealthy brothers.

Rumours painted Frances as a cold, vengeful woman who had discovered her husband’s affair and decided to end it permanently. The story of a jealous wife and her influential family ordering revenge was irresistible to the press.

The First Investigation

The initial police work was a disaster. No proper chain of evidence was kept. Witness statements contradicted each other, and the authorities seemed hesitant to challenge the powerful Stevens family.

Still, suspicion fell on Frances Hall. She admitted knowing about her husband’s friendship with Eleanor but insisted it was innocent. Her brothers also denied any involvement, claiming they were home that night.

For four years, the case went cold. Then, in 1926, a new witness emerged, one whose testimony would reignite the scandal and thrust the case back into the headlines.

The Pig Woman

The star witness was a farm labourer named Jane Gibson, known to locals as “the Pig Woman” because she raised pigs on a nearby property. Gibson claimed that on the night of 14 September 1922, she had seen four figures in the distance near De Russey’s Lane.

According to her account, she was riding her mule to investigate noises when she overheard voices arguing. She said she heard a woman shout, “Explain those letters!” followed by several gunshots. She then claimed to have seen a man and woman lying on the ground and another woman standing over them, crying.

The description seemed to implicate Frances Hall and her brothers. The prosecution seized on Gibson’s story, despite its inconsistencies. In 1926, Frances Hall, Henry Stevens, and William Stevens were arrested and charged with murder.

The Trial of the Century

The trial began in November 1926 in Somerville, New Jersey. It was one of the most sensational courtroom dramas of the decade. Hundreds of spectators packed the courthouse each day, and newspapers ran front-page coverage filled with gossip and speculation.

Frances Hall appeared calm, impeccably dressed in black, playing the part of the dignified widow. The prosecution portrayed her as a woman consumed by jealousy, aided by her domineering brothers. They suggested the siblings had lured Hall and Eleanor to their deaths after discovering their affair.

But the defence was relentless. They attacked Jane Gibson’s credibility, portraying her as unreliable and attention-seeking. Her story had changed multiple times, and her health was failing. At one point during the trial, she had to testify from her hospital bed, her frail voice broadcast into the courtroom.

Without physical evidence or consistent witness testimony, the case against the Halls collapsed. After five weeks of sensational testimony, the jury acquitted all three defendants. The verdict drew cheers from Frances’s supporters and outrage from others who believed justice had been denied.

The Aftermath

The Hall-Mills murders officially remain unsolved. No one else was ever charged, and the truth of what happened beneath that crabapple tree continues to elude historians and true-crime researchers.

Frances Hall retreated from public life after the trial, living quietly until she died in 1942. The Stevens brothers also faded from the spotlight. Jane Gibson, the Pig Woman, died in poverty, still insisting that she had told the truth.

Eleanor’s family never found peace. Her children grew up carrying the burden of the scandal that had destroyed their mother’s name. Reverend Hall’s congregation, too, was left divided, some mourning a beloved pastor, others convinced he had led his lover to ruin.

The case was more than a murder mystery. It was a reflection of its time, a period when moral hypocrisy clashed with the freedoms of a rapidly modernising America.

Echoes in The Great Gatsby

F. Scott Fitzgerald began writing The Great Gatsby only a few years after the Hall-Mills murders dominated national headlines. Though he never publicly acknowledged the case as a direct influence, the parallels are striking.

The novel’s world of illicit love, privilege, and public scandal mirrors the real-life triangle between Edward Hall, Eleanor Mills, and Frances Hall. The imagery of a wealthy man’s secret affair ending in tragedy echoed through Gatsby’s doomed love for Daisy Buchanan. Even the themes of gossip, obsession, and moral decay were part of the national conversation in the wake of the Hall-Mills trial.

Newspapers in the 1920s blurred the line between fact and spectacle, turning real lives into entertainment for a fascinated public, much as Fitzgerald would later do with his fictional characters. The murder of a minister and a choir singer, dressed up in romance and sin, perfectly captured the contradictions of the Jazz Age.

The story may have begun in the shadows of a crabapple tree, but it ended up shaping one of the most enduring portraits of American ambition and desire ever written.

The Legacy of a Scandal

A century later, the Hall-Mills murders still haunt the pages of true crime history. The unsolved case offers everything that continues to fascinate audiences: passion, betrayal, privilege, and the moral failures of respectable society.

Historians have debated new theories, from the possibility of a jealous husband to the involvement of hired men, but no theory has ever fit all the facts. What remains clear is that the case exposed the cracks in the gilded surface of 1920s America. The story of Reverend Hall and Eleanor Mills is a cautionary tale about the dangers of illusion, a theme that Fitzgerald understood better than anyone. Their deaths revealed the same truth that The Great Gatsby would later immortalise: behind the polished manners and glittering wealth, there is always the human heart, fragile, flawed, and capable of terrible things.

The Hall-Mills Murders FAQ

The victims were Reverend Edward Wheeler Hall, an Episcopal minister, and Eleanor Reinhardt Mills, a married choir singer from his parish in New Brunswick, New Jersey.

In September 1922, Hall and Mills were found dead beneath a crabapple tree, their bodies positioned together and surrounded by torn love letters. Both had been shot, and Mills’ throat was slashed.

Hall’s wife, Frances Stevens Hall, and her wealthy brothers were charged with the crime in 1926, but they were acquitted after a sensational trial that captivated the nation.

The scandal, involving illicit love, class divisions, and public hypocrisy, reflected the themes of desire, wealth, and moral decay that F. Scott Fitzgerald explored in The Great Gatsby.